I hadn’t planned to use the “Harold Lloyd More to Come”

screen grab so soon but…there will be no Crime

Does Not Pay this week. A

combination of outside interference (mi madre wanted me to accompany her to

Kroger Nation so I could lift and tote several cases of bottled water) and just

plain laziness (my old friend!) conspired to fill me with overwhelming ennui—so I

decided to shelve it and do it next week.

(Blog godmother S.Z. is probably wreaking havoc as you read this,

stealing high schoolers’ lunch money and selling reverse mortgages to

seniors.) But fret not: Thrilling Days of Yesteryear will return

next week with…stuff. Have a great

weekend, cartooners!

Thrilling Days of Yesteryear: Almost the Truth—The Lawyer's Cut

▼

Friday, June 30, 2017

Thursday, June 29, 2017

Kennedy for me

From 1931 to 1948, beloved character veteran Edgar Kennedy starred in over 100 two-reel comedies for RKO, as part of a franchise originally titled “Mr. Average Man.” Kennedy was hands down one of the finest second bananas in the history of the movies, brightening even the dullest film by merely being in it. He worked for Mack Sennett’s fun factory at the start of his movie career (he often played a Keystone Kop, and worked on a few occasions with Charlie Chaplin), and later freelanced in the 1920s before joining Hal Roach’s “Lot of Fun” toward the end of the decade as a supporting player in the classic comedies headlined by Our Gang, Laurel & Hardy, Charley Chase, and so many more. Edgar even got an opportunity to demonstrate his talents behind the camera, directing such Stan and Ollie romps as From Soup to Nuts (1928) and You’re Darn Tootin’ (1928).

|

| Harry Harvey, Florence Lake & Edgar in Contest Crazy (1948) |

The reason why even the weaker “Average Man” comedies

generate a chuckle or two is due to Edgar Kennedy, who was the undisputed

master of short-fuse stack blowing. His

signature was called the “slow burn,” a gesture where he would wipe his face in

frustration in a futile attempt to hold his temper before exploding in

rage. Edgar worked alongside many of the

great mirthmakers: Joe E. Brown (When’s

Your Birthday?), Eddie Cantor (Kid Millions), W.C. Fields (Tillie and Gus), Raymond Griffith (Paths to Paradise), Harold Lloyd (The

Sin of Harold Diddlebock), The Marx Brothers (so memorable as the lemonade

vendor who tangles with Chico and Harpo in Duck

Soup), Olsen & Johnson (Crazy

House), and Wheeler & Woolsey (Diplomaniacs),

to name just a few. He makes feature

films such as Twentieth Century (1934), San Francisco (1936), A Star

is Born (1937), It’s a Wonderful

World (1939), It Happened Tomorrow (1944), and Unfaithfully Yours (1948) a joy to sit

down with a bowl of popcorn.

Alpha Video has been releasing several volumes of Kennedy’s

RKO shorts to DVD as part of their “Rediscovered Comedies of Edgar Kennedy”

series. (I know that for many they’re

not technically “rediscoveries” in that film fanatics like the TDOY faithful are well-acquainted with

how delightful they are—but since they don’t make the rounds on any of the

classic movie channels on a regular basis some movie mavens may not be familiar

with them.) Volumes One and Two came out in 2010,

with Volume Three

following three years later and Volume Quatro released

this past April. Brian Krey was kind enough

to shoot me a screener for Volume 4, which contains ten of Edgar’s two-reel efforts

from 1934 to 1946. Some of these are the

very textbook definition of “doozy.”

The DVD kicks off with In-Laws

are Out (1934), a sidesplitting outing that has Edgar returning home from a

business trip to learn from his neighbors that wife Florence (Florence Lake) is

kicking him out of the house. The

reason? It’s Ed’s hair-trigger temper,

which is always activated by his interactions with his sponging mother-in-law

(Dot Farley) and brother-in-law (Billy Eugene).

Florence makes her husband promise that he’ll keep his anger

managed…otherwise he’s out the door. His

in-laws scheme to make him blow his top, so between those two and a mantle

clock he’s purchased that refuses to chime properly, Kennedy’s disposition is

continually challenged. One of the best

gags in this comedy (directed by Jules White’s brother Sam and co-written by Arthur

Ripley) has Edgar trudging up the stairs in his house with a priceless vase and

some blankets blocking his view of what’s ahead of him…and Eugene placing a

stepladder at the top of the staircase, resulting in Edgar’s continued

climb. The first time Kennedy makes the

trip he’s stopped by Florence before he falls off the ladder…but on the second

go-round, he falls right through the floor and emerges (somehow with the vase

intact) from a room below the staircase landing.

|

| Florence & Jack Rice scheme behind Edgar's back |

|

| Florence, Paul Maxey, Dot Farley, Jack, Harry Strang & Edgar in Brother Knows Best (1948) |

|

| Edgar & Florence in Poisoned Ivory (1934) |

|

| Edgar Hamlet (1935) |

|

| Edgar & Vivien Oakland |

|

| An interesting trade ad for A Clean Sweep (1938): Edgar doesn't have a mustache in this short, and the other male character (Eddie Dunn) never interacts with Vivien's Mrs. K. |

|

| Vivien looks over the mess the Kennedy clan made in her kitchen in Home Canning (1948), the penultimate short in the Edgar Kennedy "Average Man" series. |

Wednesday, June 28, 2017

“Heeere's Johnny!”

“And I hope when I find something that I want to do and I think you would like and come back, that you'll be as gracious in inviting me into your home as you have been…I bid you a very heartfelt good night.” Those final words rung down the curtain on Johnny Carson’s thirty-season stint as host of NBC’s The Tonight Show (or The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, as it was officially known), when “The King of Late Night” officially retired on May 22, 1992. Sadly, Carson never returned to TV save for a small vocal contribution (as himself) on an episode of The Simpsons and a cameo on Late Show with David Letterman in 1994; he left this world for a better hosting gig on January 23, 2005 at the age of 79. (Correction: I wrote too soon; Mark Murphy e-mailed me to let me know that Johnny also did a monologue on a 1993 NBC special feting Peacock institution Bob Hope on his 90th birthday. Thanks, Mark!)

|

| Johnny...we'd hardly know ye. |

Those of you who get the substation Antenna TV in your area

are aware that they added reruns of Johnny Carson (the retitled Tonight

Show) to their schedule in August of 2015 (the shows from 1972 on,

since only a handful of the pre-1972 Tonight Shows have survived due to “wiping”),

and occasionally a segment surfaces on The Greatest Cable Channel Known to

Mankind™ (their presentation, Carson on TCM, went great guns at

first before eventually doing a slow vanishing act). Time Life has released several DVD compilations—notably

the 22-disc Johnny and Friends (SRP $199.95), with 61 hours of material—and

next Tuesday (July 4) they’ll roll out a new-to-retail DVD collection of nine

classic Carson telecasts (on 3 discs—the SRP is $29.95) with the emphasis on appearances

by comedians Steve Martin, Robin Williams, and Eddie Murphy.

My good friend Michael Krause at Foundry Communications

graciously gifted me with a screener for this upcoming release, which not only

features these telecasts in their entirety (the musical guests are often

excised from the Antenna TV repeats for copyright reasons) but the original

network commercials as well. This

appealed to the old-time radio fan in me (I love to listen to broadcasts that

have the commercials intact), though I admittedly only watched one of the shows

with commercials (you have the option of watching without—something that I’m

sure would please my father if Carson reruns were his particular meat). That would be the oldest show in this

collection, a July 21, 1976 telecast on the disc spotlighting Steve

Martin. For an hour-and-fifteen minutes

(the Carson show was a ninety-minute program from 1966 to 1980) I got to

reminisce about taking the Nestea plunge and how Heinz ketchup is “slow good”

(voiceover by Casey Kasem) …not to mention seeing familiar faces like Betty

White (plugging Spray ‘n Wash) and Doris Roberts (a Glade air-freshener

commercial—she won a Clio award for those spots).

|

| I cannot come up with the name of the actor playing Doris' husband in this commercial, and it's nagging at me because I've seen him in so many other things. (It's hell getting old.) |

|

| Wild and crazy guy. |

|

| Nice threads, Eddie. |

|

| Robin Williams, circa 1984. |

|

| Comedy greatness. |

Addendum: Both the Mayor of Toobworld (Dr. Tobias O'Brien) and member of the TDOY faithful Mark Murphy have identified the actor with Doris Roberts in the Glade commercial as character veteran J.J. Barry. The blog is grateful for their tireless efforts in small screen research.

Monday, June 26, 2017

Please permit us to pause…

I had originally planned a review of an upcoming Time Life DVD

release in their The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson series for

this space today…but unfortunately, I ran out of weekend before I watched the

last disc in the 3-DVD set. I’ll have it

up on the blog Wednesday, so don’t go nipping out to the kitchen, putting the

kettle on...buttering scones...or getting crumbs and bits of food out of those

round brown straw mats that the teapot goes on.

Once again: normal blogging will resume tomorrow. (The screen grab above is from a May 21, 1982

telecast that also featured “More to Comes” with Buster Keaton, Harry Langdon,

Harold Lloyd, and Mae West.)

Friday, June 23, 2017

Crime Does Not Pay #7: “Foolproof” (03/07/36)

Well, after all the hassles with my health and the health of my computer, Thrilling Days of Yesteryear returns with our critically-acclaimed dissections of the two-reel shorts in MGM’s long-running Crime Does Not Pay series. (Spoiler: they are not critically-acclaimed.) This week’s entry, Foolproof (1936), comes to us via the team of Marty Brooks (story) and Richard Goldstone (screenwriter); both men collaborated on previous entries in the CDNP series (Alibi Racket, A Thrill for Thelma) but Goldstone had the more prolific show bidness career in that he made his way through the ranks of MGM’s shorts department as a producer (he’s credited with several Our Gang one-reelers) before graduating to feature films like The Yellow Cab Man (1950) and The Tall Target (1951). Dick later went to work for 20th Century-Fox, and in the 1960s was a producer on programs like Adventures in Paradise and Peyton Place.

Our MGM Reporter (William Tannen)—the man known cryptically

as…Jim—is also back with us; they

decided to stick him behind a microphone so he would look more reporter-ish. (He needs it, as you’ll learn in a few.)

JIM: A few months ago, I was seated in the office of Frederick Halliday—who is Captain of Detectives in a large middle Western city…

Even the names of the burgs have been changed to protect the

innocent. The (always reliable) IMDb

doesn’t technically identify the actor who portrays Cap’n Halliday, but since

Alonzo Price is listed among the players I’m gambling it’s him because a) his

name is also listed prominently among the cast in the entry for Foolproof in Leonard Maltin’s Selected Short Subjects, and 2) the IMDb

does list his place of birth as

Boston, MA (me sainted mother’s birthplace!) …and Alonzo has an accent as thick

as clam chow-dah.

JIM: Captain Halliday, I’ve been sent to you to obtain a case history of crimes from your files for presentation to the motion picture public…

HALLIDAY: I think I can do

better than that, Jim…the coroner’s jury is just doing an investigation of a very interesting case down the hall…maybe

we can sit in on the proceedings…

“But…I’m not properly dressed!”

JIM: Fine—what case is it?

HALLIDAY: The Anderson case!

JIM: Say—that sounds like a

mystery thriller…

Or something Anderson drank.

Halliday and his guest are lucky to find a couple of seats up front as

the inquiry gets underway. The actor

playing the part of the judge at the inquest is easily identified…

…it’s Stanley Andrews, the character veteran (Meet John Doe, The Ox-Bow Incident) best remembered as “The Old Ranger” on the long-running TV western Death Valley Days. Andrews’ judge is questioning one of the major witnesses in “the Anderson case”—another TV favorite…

…George Cleveland, who played George “Gramps” Miller in the early seasons of Lassie before his passing in July of 1957. Cleveland also had plum roles in such TDOY faves as It’s in the Bag! (1945—“Compliments of the management!”) and The Wistful Widow of Wagon Gap (1947), and he turns up in the Crime Does Not Pay series often, notably in 1941’s Sucker List…which I covered previously on the blog. Here’s the thing: at the time I wrote about this short in December of 2010, Cleveland’s credit at the IMDb hilariously read: “Old Man Not Beaten Up.” I swear I’m not making this up—except if you look at the entry now, the “Not Beaten Up” portion has been removed. I don’t know if I had anything to do with this or not…if on the off-chance I do have that much influence on the Internets, I offer my sincerest mea culpa because I thought it was funny as hell.

Back to the particulars of “the Anderson case.” Cleveland, as Mr. Hanson, testifies he was mowing his front lawn when a moppet named Frances came running up to report that her mother Rita (Donrue Leighton) had been hurt. Hanson finds Mrs. A bound and gagged in the bedroom, and after untying her he runs to another room to discover her husband Frank is really most sincerely dead. (And someone’s responsible!)

The coroner identified the presence of “anesthetic in the

victim’s lungs” as a contributory cause of his demise… “though not in

sufficient quantity to kill him.”

“Apparently the drug was administered to stupefy him…after which, the

murderer strangled him,” he remarks.

Further study showed that traces of that anesthetic were present on the

gag in Rita’s mouth, which apparently put her out for about six hours (the

marks on her wrists and ankles bear this out as well). Detective Whalen testifies further:

WHELAN: A routine checkup

revealed no fingerprints—nor any other clues…Mr. Anderson’s pockets had been

emptied…his watch and wallet were both missing…so were Mrs. Anderson’s

jewels…all windows and doors were in perfect order, except the front door—where apparently the burglar

made his entry by filing through a chain lock…

The Widder Anderson then testifies as to her version of events—she and husband Frank returned home from an evening soiree and as she prepared for bed in front of her dressing table, she was attacked by the assailant from behind and (presumably) chloroformed with the anesthetic (she doesn’t remember anything that happened afterward until Hanson came to her rescue). That screen grab above reminds me of the lyric in Tom T. Hall’s Ballad of Forty Dollars: “You know, some women do look good in black.”

The dowager who threw the affair that the Andersons attended, Mrs. Layton, is identified at the IMDb as an actress named Lelah Tyler—but you can’t tell me that’s not Esther Howard (Leonard Maltin thinks so, too). (The comments section awaits dissenters.) Anyway, Layton’s testimony reveals that there was a small disagreement during her party between Frank Anderson and a sebaceous individual named Terry Spencer (Stephen Chase), who starts to get a little handsy where Mrs. Anderson is concerned.

RITA: No, no, Terry…please…Terry, please stop…

FRANK (approaching the couple):

What’s the idea, Spencer? That’s my wife…

SPENCER: Yeah…I’ve often wondered about that…

(He turns his back to Anderson)

FRANK (spinning him around):

Just what do you mean?

SPENCER: I’d bet you’d like to

know…or maybe you wouldn’t…

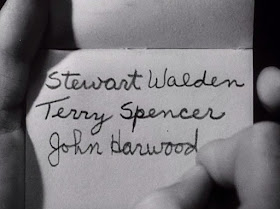

The donnybrook is just about to commence when a party guest (Niles Welch) who’s been watching the argument starts to step in and settle things…before being stopped by Rita. He’s later identified as “John Harwood,” though I should strenuously point out he is not the same guy who’s CNBC’s editor-at-large. Mrs. Layton, who describes Mr. H as “a friend of Rita’s,” assumes that’s to whom Spencer was referring when he made that cryptic “maybe you wouldn’t” statement. Judge Ranger presses her a little more, and gets her to reveal that “John thought a lot of Rita…but so did Terry Spencer!”

What amuses me about the above screen grab is that Halliday is furiously taking notes while Jim—who claims to be a “reporter”—does nothing of the sort. The first name in Halliday’s notebook, by the way, is “Spencer Walden”—the third suspect in la affaire Anderson due to his uncomfortable encounter with the victim earlier at the party:

FRANK: Why, I’ve given you

enough time already…

WALDEN: But you don’t understand…I’ll be wiped out!

FRANK (finishing his drink and

getting to his feet): Sorry, Walden…I didn’t come here to talk business…

…and learns that “getting that note extended” was of vital importance to Mr. Walden—providing plenty of motive for Stew to croak Frank. Walden claims he was home in bed:

|

| Jim will have to leave the room as soon as Halliday breaks out the oranges and pillowcase. |

HALLIDAY: Can you prove that?

WALDEN (after a pause):

Certainly I can…if I’d have come home later than midnight the clerk would have seen me…I would have

had to waken him to get in…

Next up is non-CNBC Washington correspondent John Harwood,

who works for some sort of chemical outfit as head of the sales division. Halliday has difficulty pronouncing John’s

last name due to his Boston accent; it sounds as if he’s saying “Howard”

throughout most of this short.

HARWOOD: I most certainly do

not…

“Well, unless you want to include the fact that I was shtupping

his wife.” Johnny’s got an alibi, too—he

was staying at a hotel the night of Anderson’s murder, and the next morning he

went over to his company’s warehouse to supervise a shipment. When the greasy Terry Spencer is brought in

for questioning, he, too, has a story—he was in a poker game at a roadhouse

outside of town, one that broke up at 3:30am.

JIM: They certainly all have

airtight alibis, haven’t they?

HALLIDAY: Well, I didn’t expect

them to come unprepared…

Yes, I chuckled at that.

JIM: What are you going to do

next?

HALLIDAY: Let’s see…I think we’ll

assign a man to check on Walden…I

want to find out exactly what shape

his business affairs are in…as for Terry Spencer…I want to know just who he

plays poker with every Sunday night…

As for “Howard,” Halliday assigns a couple of

plainclothesmen, Finney and Jorgensen, to pose as salesman so that they can

infiltrate Harwood’s “sales force.” Two

more detectives (one a female who watches Spencer with her makeup mirror)

shadow Spencer in a nightclub, where’s he witnessed paying off a couple of

goombahs from a large wad o’money…

As for Walden, still another dick gets the information on Walden’s business from a mousey bookkeeper who’s told not to mention anything to the boss. Walden becomes the chief suspect after Cap’n Halliday has had a look at his records:

HALLIDAY: In going over his books, we find that his business is going to the wall…a thirty-day extension on the Anderson note might have saved him…a delay, for example—caused by Anderson’s death and the settlement of his estate…and that isn’t all…Walters reports that he’s been putting his affairs in order…it looks as if he’s going to blow town…

I'm not sure I agree with you a hundred percent on your police work there, Lou. The only thing Walden is going to blow is his brains out, a delicate little matter that Halliday stumbles upon when he and Jim (I guess he’s going out on police calls now) pay Walden a little visit at his modest digs. While it looks at first glance as if Stewie committed suicide, Halliday soon rules that out since the bullet hole was in his forehead and the Captain believes it’s a little awkward shooting yourself that way (most suicide attempts occur at the temple, he tells Jim). “Guess that’s why he was putting his affairs in order,” notes Jim inappropriately. (The Walden family is gonna love him at the funeral.) Halliday also observes that Walden was killed at nearly the same time on the same day as the unfortunate Frank Anderson—“I don’t think that’s a coincidence at all.”

So, the finger of suspicion is redirected back to Spencer and Harwood. Halliday has a funny line when talking to the detective who’s been birddogging Spencer; the dick tells him that everyone in the suspect’s poker game will swear he was there the entire time and the Captain cracks: “That don’t mean much—those guys will swear to anything.” (Terry is quite friendly with “the mob” …though that could also describe the Chamber of Commerce, to be honest.) But “Jorgy,” in conversing with Halliday, mentions that Harwood’s first stop on his sales route is in a town with an airport…and that gives Freddie an idea…

Halliday and Jim pay the Widder Anderson a visit, where the Cap’n tells Rita that they’re closing in on the man responsible for killing her husband. “I can assure you an arrest within 24 hours,” he informs her. Rita is concerned that the assailant will get away, but the cocky Halliday tells her not to fret. “He’s completely surrounded.”

He had a reason for telling her this—he now knows it’s Harwood, and he further knows that Rita was in on the caper from the beginning when she foolishly calls John to tell him to be careful and your friendly neighborhood police department has tapped her phone.

Harwood is picked up in the same fashion he utilized when he murdered Anderson and Walden. He snuck out of his hotel room and hid in the back of one of the company’s truck, covering himself with a tarp that he instructed the warehouse guys to place over the shipment beforehand. When the truck made its first stop, he exited the back of the vehicle and took a plane from the airport to Marion, where both Anderson and Walden lived. In the case of Frank, he instructed Rita that he would knock her out with the anesthetic so it would look like a home invasion—though when she’s confronted by the police she swears she had no idea John was going to send her hubby to The Happy Hunting Ground. So why did he kill Walden? “Like all criminals, you couldn’t stop at your first crime,” sneers Halliday. Just like Lays’ Potato Chips—you can’t eat just one. (Rita and John killed her husband for the insurance—the oldest game in the Big Book O’Crime.)

JIM: Rita Anderson was sentenced

to twenty years in the Women’s State Penitentiary…

Presumably under the supervision of the

happy-go-lucky female warden in A

Thrill for Thelma.

JIM: …John Harwood is in the

death house now…

When he’s not hosting Speakeasy

with John Harwood on CNBC Digital.

JIM: …waiting for the law to

exact the final penalty for his foolproof crime…for foolproof it was, only in

the sense that it proved an ingenious criminal…a fool…

Sorry I cut this one so short this week…but my ass was starting to get numb. Next time, Crime Does Not Pay goes to the Academy Awards with the first of two Oscar-winning entries in the series, The Public Pays (1936). G’bye now!

Thursday, June 22, 2017

Lubitsch of Arabia

Janaia (Pola Negri) is a breathtakingly beautiful dancer who travels with other performers in a caravan…and who’s attracted the attention of a Bagdad slave trader, Achmed (Paul Biensfeldt). Achmed has been commissioned by Zuleika (Jenny Hasselqvist), the current favorite in a harem maintained by “The Mighty Sheikh” (Paul Wegener), to procure women for her hubby…because she no longer wants to be the favorite, preferring instead the romantic attentions of Nour-Ed Din (Harry Liedtke), humble (and handsome) clothes merchant. His Sheikhness, learning of Zuleika’s perfidy, condemns her to death…but she is spared when the Sheikh’s son, Sheikh, Jr. (Carl Clewing), pleads for her life. Janaia is not so fortunate—the cruel despot bumps off both her and Sheikh, Jr. (they were having a little thing on the side) but before he can add Zuleika and Nour-Ed Din to the body count he is dispatched to the Great Beyond by the hunchbacked Abdullah (Ernst Lubitsch), who’s avenging the murder of Janaia.

All this palace intrigue has been condensed into a

fifty-minute cut-down of Sumurun, a

1920 melodrama directed by Ernst Lubitsch before he emigrated to the U.S. and exhibited

“the Lubitsch touch.” (“Sumurun” is the

name of the Zuleika character in the original German movie.) The movie would be released in America the

following year and retitled One Arabian

Night; the (always reliable) IMDb lists the movie’s running time as a longer

eighty-five minutes (another DVD version clocks it at 105). The 50-minute version is from an Alpha Video release that came out in mid-May.

The shorter running time on the Alpha DVD really hurts the

viewing experience, sad to report. It

makes One Arabian Night confusing

and often difficult to comprehend, which is a shame because I had heard a good

many positive things about the picture and I was looking forward to sitting

down with it. It’s not entirely

unrewarding; it’s interesting early Lubitsch (his later themes of infidelity

and naughtiness are on full display in this tale based on the pantomime by

Friedrich Freksa), and it also showcases the appeal of Pola Negri, who would go

on to a prolific career as a silent screen siren. It was with the success of Night in the U.S. that Mary Pickford was

encouraged to invite the director and his star to make movies in Tinsel Town. Lubitsch would continue to direct classics

like Trouble in Paradise (1932) and Ninotchka (1939) until his death in

1947 (his valedictory feature, 1948’s That

Lady in Ermine, was assigned to Otto Preminger after Ernst died during

production) but Negri, despite box-office hits like Forbidden Paradise (1924—directed by Lubitsch) and Hotel Imperial (1927—the only other

Pola film I’ve seen), went back to Europe to work toward the silent era (her

thick Polish accent would have been a problem)—only resurfacing in two later American

films, Hi Diddle Diddle (1943) and The Moon-Spinners (1964, her final

movie).